Fig. 1- The Partisans

On a spring day in 2003 after having recently arrived in Massachusetts, a friend

visiting from California and I set about “seeing the city” from

one of the infamous WWII amphibious ducks on the “duck tour.” A

happy and humorous adventure, my breath was suddenly taken away from me as there,

darkening my happy mood was a stark and disturbing work of art on the common

that reached out its ethereal fist and punched me in the gut.

The

spring and trees were blooming, but none of it mattered compared to these four…

no, five… gaunt and disturbing horsemen trudging their way across the

common (fig. 1). What did it mean? As I turned around in my seat to get another

look, all I could think of was Native Americans, returning from a battle in

which they fought for their beliefs and lives. Once again, they were beaten

into retreat, starving and somber. I wasn’t entirely off-base –

the work of art known as “The Partisans” was created by sculptor

Andrzej P. Pitynski, as a tribute to guerrilla freedom fighters everywhere.

Pitynski was born in 1947 to Polish parents who were these “Partisans.”

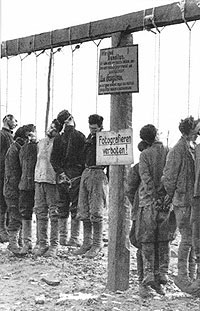

Partisans were the names given to Jewish, Polish, and other persecuted guerilla

fighters who hid in the forests of Europe fighting the Nazis. They did the best

they could, on foot or horseback, starving and many times dying for their beliefs

that they should be able to live and enjoy the same freedoms as anyone else

(fig. 2). The term “partisan” takes on a double meaning, however.

The more morally neutral term meaning is a term meaning one who is a “volunteer

combatant” who has chosen to take sides and takes an active part in resisting.

The more negative connotations of the word, however, implies that one is a partial,

unreasoning, and at times fanatical advocate to a cause.

|

|

| Figure 2 – Partisans

in WWII Russia, and Partisans on Boston Common |

Andrzej P. Pitynski came to the United States in 1974, and sculpted the work

in 1979. The cavalry was meant to be displayed in Warsaw, Poland, but due to

communism and the disturbing nature of the work, it was not welcomed. The work

was without a home until it was placed on the Boston Common in 1982, where is

resides today as part of the “Immigrant Heritage Trail.”

Technically on loan to the city, the sculpture was originally displayed near

Brewer Fountain across from 131 Tremont Street. According to urban legend, Kevin

White (then the mayor of Boston) didn’t like it there, and had it moved

to the common. Kevin White is not the only critic who didn’t

like the sculpture, apparently. While looking for information about the sculpture,

I came across this rather harsh assessment of the sculpture:

The heartfelt visages on the unrepentant political renegades of our late-19th-

and early-20th-century statues have been replaced by depersonalized, often

didactic abstract memorials to citizens who were wiped out...

...Partisans is intended as a tribute to guerrilla freedom fighters everywhere;

the artist, in other words, had no war, no names, nobody specific in mind.

And it reads as generic. Five bedraggled men on horseback, their postures

hyperbolic as a press release, hold their bayoneted rifles like slim, sharpened

crucifixes. Featureless and interchangeable, they register like a public-service

announcement on the dangers of overexertion.

Fig. 3 - Reaching out for... what?

At first these statements perplexed me, because it seemed perfectly obvious

that this was no “generic” work. After thinking about it,

it is true that I only understood the specificity of the work in regards to

partisans like Pitynski’s parents after having done some research. However,

the fact that it initially registered (strongly) to me as having been another

group of persecuted people with the conviction and will to keep fighting, says

to me that the idea is still there, even if it is interchangeable for whom it

stands for. In doing so, it satisfies the idea of memorializing guerrilla freedom

fighters everywhere.

A very vertical and horizontal piece, one would presume that there is not

much movement to the piece. However we see a quiet, determined plodding on,

and the horses and riders seem to be moving, even while on the edge of death.

From different angles, however, the horse’s necks crane in every direction,

seemingly seeking something out – perhaps food… rest… death?

(fig. 3)

Fig. 4 - Horses reach forward to meet the spectator

The horses struck me the most poignantly, as they are at eye-level, with such

forlorn faces that you wish to reach out and try to comfort them (fig. 4).Gaunt

and starving, you feel sorrow as their necks crane, reaching out to pick fruit

from barren and nonexistent branches. Not even the m&m candies placed in each

of their mouths (fig. 5) by some facetious passer-by subsides the overwhelming

feeling of hopelessness.

Fig. 5 - It's going to take more than M&M's...

Manes and tales hang limply, while open mouths gasp for air, or fruitlessly attempt

to cry out. Overexerted, nostrils flaring, and eye sockets empty and hollow, these

horses are a frightening site, reminding one of the Book of Revelations

in which four horsemen herald the end of the world. The spindly legs and pole-arms

jutting straight up vaguely remind one of the forests where these fighters would

hide. The rough blackened aluminum could also remind someone of the harsh elements

that would attack these vagabonds, such as rain, mud, snow and ice.

Looking up, one is dwarfed by the grim-reaper riders, sitting in their saddles

with awkward rigidity. They have no eyes – just sunken holes in their

faces, their gaze cast downward – in sleep, in weakness, in starvation,

or in weariness. In most cases, they don’t even hold on to their mount.

Awkwardly upright, with slouching bent necks, it almost gives the impression

that they are dead and strapped to their mounts and the pole-arms protruding

from the side (figure 6).

|

|

| Fig. 6 - Head bowed in prayer? |

Fig. 7 - ...or awaiting his fate? |

Each new viewing angle also takes on new meaning. Details are left obscured, and

the entire work is left rough and implicative. From certain angles, the pole-arms

even take on a new function – a noose around the necks of these insurgents

(fig. 6), serving as a reminder of the cruel fate of any such rebel who is captured

(fig. 7). The partisans’ quest seems daunting, if not impossible, yet they

still continue forward.

Seeing this sculpture calls to mind the oppressive and

often inhumane regimes that generate such opposition. It speaks of the many

movements for freedom in the centuries since the word "partisan" was

first used in Italy to describe volunteers and freedom fighters. And it reminds

us of the passionate commitment of those who took to the mountains and forests

during the Second World War. Unlike the quislings who did the Nazis' bidding,

and the many who averted their eyes, these partisans had the nobility and the

courage to resist. The sculpture evokes, too, the humane courage of the resistance

movement in postwar Poland.

While surveying the work on the common, I was met by some British tourists,

who were equally impacted by this sculpture, and we briefly chatted about it.

“Why do you think their heads hang in such a manner?” the one gentleman

asked. “Because they’re weary!” This seemed to be the obvious

answer.

“They look hungry,” stated his wife. “Do you think they’ve

found what they are seeking?” he queries. I think for a moment and then

answer, “The battle is never over – the quest for freedom will always

continue.” The gentleman agreed, “Indeed, so it does.”

Fig. 8 - Afghani guerrilla fighters

This little repartee on the common showed me just how much impact the sculpture

had, and the influence it had on its hundreds (thousands?) of daily viewers. The

fact that this discourse took place with a citizen of another country –

one which allies itself with the United States in the common cause of freedom,

struck me as irony at its best. Both of our countries have soldiers across the

seas trying subdue partisans and citizens alike in the name of freedom, yet are

constantly amazed at their resiliency and persistence. As this sculpture conveys,

it is not easy to stop someone with a cause to fight for (fig 8). They will find

a way to trudge along and keep going.

The overwhelming consensus of the day is that it is most certainly a “powerful”

piece. In the hour or so I spent pacing around, crawling under, standing on

tip-toe, and viewing the Partisans from every angle, something besides its superficial

characteristics caught my attention - its impact and on people walking by. Except

for the very few self-absorbed or jaded city-dwellers who have no doubt passed

the spot hundreds of times, the sculpture stopped every single person or group

who walked past it. They all paused to absorb and reflect these lone and weary

horsemen on the common.

Though these works have fans and foes to varying degrees,

they are equally clear about the human toll of fighting for what one believes

in — a message both timely and timeless.

Footnotes:

Bok, Sissela.

“Excerpts from A Strategy for Peace, Chapter 1: Partisanship and Perspective

- Five Horsemen.” The Peace Prize Forum. <http://www.stolaf.edu/nppf/2000/resources/strategy.htm>

Maihos, John.

“Freedom Fighters - Polish Artist Captures the Struggle.” About

dot com. <http://boston.about.com/od/historyandnature/a/freedom_fighter.htm>

Millis, Christopher.

“The good, the bad & the ugly - An opinionated, irreverent look at Boston's

public art.” The Boston Phoenix, August 21-28, 1997. <http://www.bostonphoenix.com/archive/art/97/08/21/PUBLIC_ART.html>

Greenwood,

David Valdes. “Art and about - Ten not-to-be-missed works and exhibitions.”

The Boston Phoenix, July 23-29, 2004. <http://www.bostonphoenix.com/boston/news_features/dnc_04/misc/docs/documents/03988919.asp>

Photocredits:

|